At 81 years old, Sly Stone is finally experiencing a long-overdue and well-deserved resurgence. The year 2023 marked the release of his memoir, Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin), a book that garnered widespread acclaim, including from this critic, and was met with much celebration.

For decades, Sly was regarded as one of music’s most infamous cautionary tales. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, he and his band, the Family Stone, dominated American popular music. However, by the mid-1970s, Sly had spiraled into a harrowing cycle of drug abuse.

In the years that followed, his once-revered name became synonymous with no-shows, humiliating public appearances, and a seemingly endless series of arrests.

Eventually, he vanished from the spotlight—his last studio album of original material was released in 1982, and over time, his well-being and whereabouts became the subject of whispers and speculation, when they were spoken of at all.

So, when Sly reemerged with his autobiography—seemingly clean, lucid, and prepared to step back into the public eye—it felt like a true rebirth.

That sense of resurrection continues with Questlove’s new documentary, Sly Lives! (also subtitled The Burden of Black Genius), which begins streaming on Hulu this Friday.

(Questlove’s publishing imprint, Auwa Books, was also responsible for publishing Sly’s memoir.) Sly Lives! is an exceptional film—intelligent, stylish, and brimming with remarkable footage and insightful commentary, both musical and personal. While Sly himself does not appear in the film—despite what the title might suggest—his presence is strongly felt.

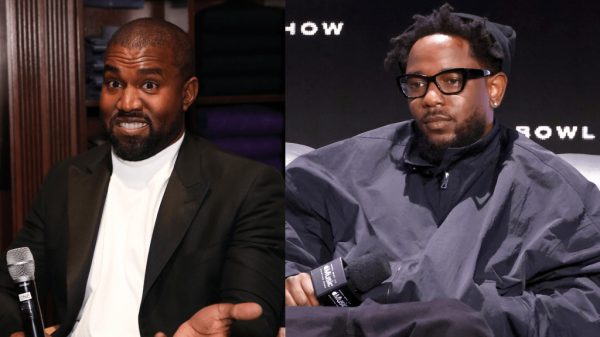

Several of his adult children make appearances, implying the project had his approval. In his absence, Questlove has assembled an extraordinary lineup of interviewees, including Nile Rodgers, André 3000, George Clinton, Chaka Khan, Clive Davis, and three original members of the Family Stone: saxophonist Jerry Martini, bassist Larry Graham (who younger audiences might recognize as Drake’s uncle), and drummer Greg Errico.

Meanwhile, trumpeter Cynthia Robinson, who passed away in 2015, is represented through archival interview footage.

As the film explores Sly’s early years, it presents a vivid, if relatively conventional, account of his rise to prominence. It delves into his childhood in the Bay Area, his formative musical experiences in church and in racially and gender-diverse high school rock ’n’ roll bands, and his early days as a charismatic radio DJ—a fascinating facet of his life that could warrant an entire film of its own.

The documentary also chronicles his initial forays into the music industry as a songwriter and producer, including his work with the acid-rock band the Great Society, which featured future Jefferson Airplane frontwoman Grace Slick. (Legend has it that Sly quit the sessions in frustration over the band’s lack of skill.)

It is fitting, then, that Sly Lives! truly soars when the Family Stone does. The commercial failure of the band’s major-label debut, 1967’s A Whole New Thing, led Sly to refine his approach for broader radio appeal. This shift resulted in “Dance to the Music” and a subsequent onslaught of hits.

The 1969 release of the platinum-selling Stand! and the band’s legendary Woodstock performance that same year mark the height of their fame. However, there are early signs of trouble—Jerry Martini recalls a literal mountain of cocaine consumed backstage before their iconic set.

The film devotes significant time to 1971’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On, widely considered Sly’s magnum opus and one of music’s most unfiltered chronicles of both personal and professional collapse. It then turns, with unflinching but never exploitative detail, to his steep decline from stardom.

Sly Stone

Sly Lives! excels in its focus on musical intricacies—perhaps even more so than Questlove’s Oscar-winning Summer of Soul. The documentary feels like a film made by a musician for musicians.

Interviewees provide illuminating commentary on Sly’s vocal arrangements, including his tendency to alternate between unison and harmonized vocals.

They also examine his singular compositional style on classics like Stand!, as well as his pioneering use of an early drum machine on “Family Affair,” the first major American pop hit to incorporate the device.

Among the most engaging moments are legendary producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis breaking down the musical architecture of some of Sly’s most innovative recordings with thrilling precision.

The documentary also explores the weight of Black superstardom—the paradoxical reality in which Black artists are simultaneously celebrated as exceptional yet burdened with representing their entire race.

It highlights the ways scrutiny is often harsher for Black artists and how public fascination with their downfall can be especially intense. Some of the most striking insights come from Questlove’s longtime collaborator, D’Angelo—an artist whose immense talent, tumultuous career, and reclusive tendencies invite comparisons to Sly’s own journey.

Since watching the film, I’ve been reflecting on its subtitle, which lingers in my mind as both evocative and elusive—particularly the way the word “Black” is crossed out, leaving simply the burden of genius.

Musical genius is a difficult concept to define. While I don’t believe it’s just a marketing buzzword, I’m also not convinced it’s an immutable trait. Even those with extraordinary talent experience ebbs and flows of inspiration.

Stevie Wonder is widely regarded as one of the most gifted musicians alive, yet most would agree that his work in the 1970s far surpasses what he has produced in the decades since. Similarly, Prince’s 1980s output is generally considered superior to his work in later years. No musician’s career is an unbroken series of triumphs.

Sly Stone’s career arc is especially perplexing. His meteoric rise was breathtakingly high yet relatively brief, and his downfall so dramatic that it’s often attributed solely to drug use. While that explanation is understandable, it is also somewhat reductive.

Both Sly Lives! and his memoir make clear that his substance abuse began long before it visibly affected his music and behavior.

Several interviewees, particularly his former bandmates, suggest a more complex picture—one in which Sly’s increasing drug use may have stemmed from deep-seated insecurities about his waning creative direction.

He was the only one who could write “Everyday People,” “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin),” and “Family Affair”—but he could only write them once.

Sly’s music, especially There’s a Riot Goin’ On, was so influential throughout the 1970s—its raw, surreal funk shaping everything from R&B to rock, disco, and jazz—that one can only imagine how disorienting it must have been for him to begin the decade at the pinnacle of the industry and end it as a perceived relic.

This raises the question: is genius an inherent trait, or is it a fleeting, fragile state? The answer to that question is as heartbreaking as it is fascinating, and Sly Lives! can only hint at it. That story is Sly’s alone to tell, and no one could fault him for choosing not to share it.